"You don't have to be crazy to work here, but it helps."

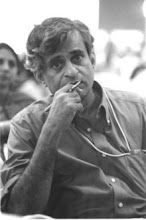

So read the sign outside Russy Karanjia's office in Blitz. He passed away on February 1, exactly 67 years after he founded one of India's most powerful publications. He was 95. The tabloid died a few years before him. Karanjia the man would have been touched by the obituaries in the press. Karanjia the editor would have rejected most of them as unfit for publication. "Too reverential," he would have grumbled. "Where's the spice?"

He was the last of the buccaneer editors. "Free, Frank & Fearless," roared our masthead. We were not always fearless. We were sometimes too free for our own good. And we were often obnoxiously frank. But Blitz was always readable, thanks to an editor with an unrivalled instinct for what would make news to an incredibly diverse readership, from a jawan on the Chinese border to striking textile workers in Mumbai. A genius who gave some of Indian journalism's greatest names their first break, or a platform to build from. That includes R.K. Laxman. Blitz was also the paper where K.A. Abbas ran his legendary Last Page column unbroken for more than 40 years. Though the English tabloid was the oldest, Blitz also appeared in Hindi, Urdu, and Marathi. Karanjia also founded and ran a morning tabloid called The Daily for some years. His daughter Rita ran the high-circulation Cine Blitz.

Blitz was an anarchist's parliament. And we had two of everything. What we did not have on staff, we had in equally eccentric contributors. We had the world's least successful astrologer. The stars he consulted were mostly those dancing around eyes lit up by liquor. Often staffer wrote fanciful forecasts under his name when he passed out from too much stargazing. Karanjia, who pioneered the political astrology beat, would bully him into making predictions (which Karanjia favoured) on who would sweep the elections. When these bombed, he would chew him out: "What sort of astrologer are you? Can't you get anything right?" The shaken oracle would totter off seeking what we at Blitz called Spiritual solace. After one proonged absence the last page of Blitz ran words to the effect "Jupiter may be in the house of Mars, and Saturn in the house of Venus, but it will be be a while before Pandit Astro rolls into the house of Karanja." He was back that afternoon.

Blitz had its own style. Embedded journalism, never. Embellished journalism, ah well, every now and then. Karanjia was above all a great storyteller. He spoke even better than he wrote - and he was an excellent writer. He had a wicked sense of humor, too. He once sent me - underlined and with exclamation marks - an aphorism from Richard Ingrams, editor of Private Eye: "Never let the truth stand in the way of a good story."

Yet Blitz carried more racket-busting reports and giant political scoops than anyone else. Chief Ministers, Cabinet Ministers, and Governors were laid low by a paper that had amazing access to everything. Investigations, stings, exposes, almost anything the press now celebrates, first happened with Karanjia. He was also the first editor who took photographs and visuals seriously. Look at their quality in Blitz at a time when most papers ran blotched images where it was impossible to tell Khrushchev from his wife.

He also stood by us when the powerful complained, though sometimes in outrageous fashion. Once a politician, now big at the Centre, called to complain about a damaging - and true - story on his land fraud, run as a "Blitz Exclusive." I walked into Karanjia's cabin in time to hear him tell the man on the phone: "I was away, you know, that story was run by my hot-headed deputy, I must discipline him." I raged at him: "How could you do that? It was your story, not mine. The man will now hate me forever." He was unruffled. "He hates you, anyway, dear fellow, and you don't love him either. I've known him since he was a lad and must maintain some equation with him. I don't see what you're complaining about."

He was an instinctive gambler on big issues: Which way to go on technology? Who would win the elections? What was the Big Idea to back? What could we get Parliament fighting about? Some of his gambles succeeded beyond belief. Some left us gasping in a quagmire. He never sought scapegoats for failures, though (except with the astrologer), always taking personal responsibility for things going wrong. I should know. It never happened during the 10 years I was his deputy chief.

Karanjia brought the April Fool hoax to the Indian press. His biggest April 1 coup came when The Daily's front page announced the sale of The Indian Express to A.R. Antulay. At a time when the Express was, in fact, running a campaign against him. Amidst a chaos of jangling phone lines, furious denials and total bewilderment in the city, an incensed Ramnath Goenka warned he would sue us. Karanjia loved that threat. And he did not mind taking on both powerful and dangerous people. As he told me of one, "Oh I say, if you call him a crook, do put a question mark to it. That helps with the libel stuff, you know."

There were periods when I fought with him every morning, but he always made me laugh by the end of the day. Like when I stopped the practice of the pin-up girl on the Last Page. A handwritten note from Karanjia to me ran: "Dear Sainath, now that we are emulating the Vatican Gazette, do you have any further ideas to perk up the paper

Like its editor, Blitz was internationalist. Countless Indians followed the wars of liberation in Vietnam, Africa and Latin America, through Blitz. His great hero was Fidel Castro (whose photo remained on his desk till the last day he went to office.) The Americans hated him and denounced him as a Soviet stooge.

At the height of the Sino-Soviet hostility, Karanjia managed exclusive interviews with the leaders of both the USSR and China (including a rare meeting with Zhou en Lai.) He also had one with the Pope in the same period. His early interview with Castro, though, was very Blitz. Landing in the confusion of revolutionary Cuba, Karanjia was mistaken for the Indian envoy, an error he did little to correct. Castro held up his hand and waved to the crowds at meetings. "Oh, I was in the doghouse a bit when it came apart," he told me. But Castro's own sense of humour triumphed and Karanjia returned with one of the most important interviews of his life.

Blitz had some superb small town correspondents who, unlike the astrologer, were pretty good at calling elections. For years, it had lakhs of readers, and more of them writing to the editor than in any other paper. Readers who would raise lakhs of rupees for causes ranging from poor children needing costly surgery to funds for Vietnamese freedom fighters. Karanjia, who knew giants and was once called a "chronicler of revolutions, a biographer of revolutionaries," never lost sight of little people. It was he who taught a generation how to make a big story of little people. He was the only editor of a big publication in India who supported the massive textile strike of the early 1980s for the full 19 months it lasted.

No editor was more accessible. Anyone could walk into Blitz - and they often did. From levitating ascetics to poor municipal cleaners complaining about working in the sewers - all could meet the editor directly. No vast security apparatus. Even policemen turning up to serve him with summons would have tea with him and return pretending he was untraceable.

Karanjia's unfailing look at the funny side of everything rubbed off on the rest of us. Blitz never lost its sense of fun even when threatened or attacked physically. This was an office where crank callers were welcome entertainment and those hurling death threats were baffled by the response they got. As my late colleague Habib Joosab told one caller: "No, you cannot kill us Mondays or Tuesdays. Those are our press days, don't you know we're busy?"

The staff were his extended family. As patriarch, he could yell at us. Those yelling back were generously tolerated. No one was victimized. To know this man was to love him.

In the mid-1990s, long after I had left the job, he had an accident that damaged his memory. At the hospital I was told he was not recognizing anyone. In his room he greeted me with: "Good evening, Sainath. Have you put the paper to bed? You know I hate going late." I hadn't the heart to remind him I had left Blitz ages ago. I assured him all had been done. Here was a man who, when he had forgotten almost everything, remembered he was a journalist and an editor. Nothing could erase that identity.