Tuesday, December 25, 2007

India 2007: high growth, low development[24/12/2007]

Even nations that are far below us in the HDI rankings — and which have nothing like our growth numbers — have done much better than us on many counts.

The good news is that India’s falling to rank 128 in the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is not really a decline. Even though it was ranked 126 last year. So say unnamed officials (at least, according to a report in one newspaper). It seems the truth is that we would have been 128 anyway, even last year, “had updated data been used for other countries.” In short, we have not really slipped in rankings, you know, we were this bad all along. In Mumbai argot: “We are like this only.”

To begin with, the rank of 128 puts us in the bottom 50 of the 177 nations that the UNDP Human Development Report looks at. Treat Adivasis and Dalits as a separate nation and you will find that nation in the bottom 25. Or subtract our per capita GDP ranking from the process and watch India as a whole do a slide. Meanwhile, even nations that are far below us in the rankings — and which have nothing like our growth numbers — do much better than us on many counts. So even if our HDI value took a tiny step up from 0.611 last year to 0.619, it means other nations did much better than us. And hence we went down to rank 128 this year.

Each year since 1990, the Human Development Report (HDR) of the UNDP publishes the Human Development Index (HDI). This index “looks beyond GDP to a broader definition of well-being.” The HDI seeks to capture “three dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life (measured by life expectancy at birth). Being educated (measured by adult literacy and enrolment in primary, secondary and tertiary education). And third: GDP per capita measured in U.S. dollars at Purchasing Power Parity (PPP).”

Let us look at where we stand in the rankings of the index. El Salvador, which saw a bloody civil war for over a decade from the 1980s, ranks 25 places ahead of us at 103. Bolivia, often called South America’s poorest nation, is 11 steps above us at 117. Guatemala, nearly half of whose citizens are poor indigenous people, saw the longest civil war in Central America. One that lasted close to four decades and which saw 200,000 people killed or disappear. That too, in a nation of just 12 million. Guatemala ranks 10 places above us at 118.

In Africa, Botswana — ranked below us in the 2006 HDI at 131 — climbed four places above us at 124 this time. It replaced fellow African nation Gabon which quit that slot to move upwards to 119 this year. (Gee, their updated data arrived on time. Must be using a different courier service.) The Occupied Palestinian Territories, with all their woes, slipped six places to 106. Still well ahead of India.

In Asia, countries like Vietnam — victim of the bloodiest conflict since World War II — rose further in the charts, to rank 105 this year. Sri Lanka, of course, is way ahead of us at 99. So are nations like Kazakhstan and Mongolia. They too have risen in the ranks. The former from 79 to 73 and the latter from 116 to 114.

Note that some of these nations rank up to 30 slots above us. Others fall within 30 nations below us. Not one of them has had our nine per cent growth. Few of them have been touted an emerging economic superpower. Nor even as a software superpower. Not even as a blossoming nuclear power. Together, they probably do not have as many billionaires as India does. In short, even nations much poorer than us in Asia, Africa and Latin America have done a lot better than we have.

India rose in the dollar billionaire rankings, though. From rank 8 in 2006 to number 4 in the Forbes list this year, but we slipped from 126 to 128 in human development. In the billionaire stakes, we are ahead of most of the planet and might even close in on two of the three nations ahead of us (Germany and Russia). It will, of course, be some time before we erase the national humiliation of lagging behind the top dog in that race, the United States. (Which, by the way, dropped from 8 to 12 in the HDI rankings this year.) The Cuban example

Cuba has zero standing in the roll call of billionaires. In terms of per capita income, it ranks low in the world. But when it comes to human development, it ranks 51 — that is, 77 places ahead of us. It figures in the HDI’s ‘High Human Development’ group. This is a nation which has faced a huge economic blockade since its birth. U.S. sanctions ensure that almost everything is costlier in Cuba than in many other nations. In per capita terms, it spends four per cent of what the U.S. does on health but achieves better outcomes on most of the vital parameters of that sector. Despite its many disadvantages, it achieves a better HDI rank than Mexico, Russia or China. (All of which have gained more billionaires in recent times.)

But there is hope. Our top 10 billionaires are doing fine. “Their collective wealth has soared 27 per cent since July this year,” The Times of India told us on its front page on October 8. The headline said they’d got “richer by $65.3 billion” in just three months since July. That is, by more than Rs.119 crore an hour. Or not far from Rs.2 crore every minute. Of the 10, the TOI tells us, Mukesh Ambani alone “increased his wealth by roughly Rs.40 lakh every single minute.”

It is doubtful if the wages of agricultural labourers went up by just Rs.40 (just 40, not lakhs) in years, let alone by the minute. But then we rank fourth in super-rich and 128th in human development. Most of our billionaires seem to be from Mumbai, also home to a quarter of India’s $100,000 millionaires. Mumbai is the capital of Maharashtra, perhaps our richest State on many counts. One that has seen close to 32,000 farmers commit suicide since 1995. Also a State where rural poverty has gone up even in official reckoning.

Meanwhile, the UNHDR records that almost a third of India’s children, or 30 per cent, are below average weight at birth. In Sierra Leone, ranked at 177, rock bottom of the Human Development Index, it is 23 per cent. In Guinea Bissau and Burkina Faso, ranked 175 and 176, children with low birth weight account for 22 and 19 per cent. Even in Ethiopia, ranked 169, the figure is 15 per cent. So we’re down there with the bottom five on that count.

Amongst children under the age of five, 47 per cent in India are underweight. In Ethiopia, that is 38 per cent. And in Sierra Leone, 27 per cent. We are home to the largest number of malnourished children in the world. When it comes to child nutrition and literacy, we jostle for space with the nations ranked lowest in HDI in the planet. And mostly we even beat them. ‘Statistical glitch’

This week’s papers report a curious new development. One which might further impact on our ‘rank.’ They report a World Bank study as saying that the Indian and Chinese economies might be smaller in size than we believe. Maybe almost 40 per cent smaller, says The International Herald Tribune (December 9, 2007). “What happened was a large statistical glitch,” says the IHT. But it’s a glitch that matters. “Suddenly the number of Chinese who live below the World Bank’s poverty line of a dollar a day jumped from about 100 million to 300 million.” It turns out the overpaid elite number crunchers have been using obsolete data for a very long time.

The Bank’s own survey lists new purchasing power parities for 100 countries benchmarked for the year 2006. Well, India figured in the study for the first time since 1985 and China for the first time ever. And so? India’s GDP in PPP terms, the TOI notes, was $3.8 trillion in 2005 before the new study. Going by the new data after the revision, it stands at $2.34 trillion. (In nominal dollar terms, roughly $800 billion.) Boy! These updated data are a nuisance. First it turns out we should have been HDI rank 128 last year, too. Now we learn that our economy is a lot smaller than we imagined. As the IHT says, “This is not a mere technicality.” It shrinks the relative size of developing economies by quite a bit. India’s GDP per capita (PPP) falls from $3,779 to $2,341 with the new data. Also, as the TOI sadly notes: “We ain’t a trillion dollar economy yet.”

It is not clear yet how agencies other than the Bank, like the UNDP for instance, were working with PPP. Were they using updated measures or the old data? If the latter (which seems the case), and given India’s entry in the Bank survey is recent, even our awful HDI performance could get worse. The captain has switched on the seat belt sign. Buckle up: we could be landing soon on the updated numbers.

Tuesday, November 27, 2007

Maharashtra ’s head-in-the-sand syndrome[the hindu-27/11/2007]

“Committing suicide is an offence under the Indian Penal Code. But did we book any farmer for this offence? Have you reported that?” — Maharashtra Chief Minister Vilasrao Deshmukh on farm suicides in Vidharbha.

That is the Chief Minister’s response to media questions on the ongoing farm suicides in Vidharbha. He has gone on record with that statement in an interview. (The Hindustan Times, October 31.) Leave aside for the moment this incorrect reading of the law. Mr. Deshmukh clearly believes he has been merciful towards those committing the ‘crime’ of suicide. Thanks to his government’s generosity, close to 32,000 farmers in his State wh o have taken their lives since 1995 go scot-free. Imagine what would happen should he decide to book them for their ‘crime.’ For the record, on average, one farmer committed suicide every three hours in Maharashtra between 1997 and 2005. Since 2002, that has worsened to one such suicide every two-and-a-quarter hours. Those numbers emerge from official data. This could be the State’s worst tragedy in living memory.

Of course, the question arises: who would he punish if he decides to enforce what he believes is the law? And how would he do so? Would their ashes be disinterred from wherever to face the consequences of their actions? Would the awful majesty of the law be visited upon their survivors to teach them never to stray from the path of righteous conduct? Or — more likely — would his government set up yet another commission to look into the matter?

Under Section 309 of the Indian Penal Code, attempting suicide is a crime. A suicide effort that succeeds places the victim beyond Mr. Deshmukh’s reach anyway. Beyond anything for that matter. As one of India’s foremost legal minds says: “the odd thing about suicide in India is that failing to commit it is a crime. One who succeeds in it is obviously beyond punishment. But the one who fails in his attempt to commit it could be in trouble. You could then be booked for ‘attempted suicide,’ an offence punishable by fine and even imprisonment.”

Abetment to suicide (Section 306) is also a crime. One that places Mr. Deshmukh’s government in the dock if we persist with this logic of ‘punishment.’ His Ministry has been widely criticised on the farm suicides in this State. Many point to the rash of suicides that occurred soon after the government withdrew the ‘advance bonus’ of Rs.500 per quintal of cotton in 2005. A move that tanked cotton prices and brought disaster to lakhs of farmers in the State.

Worse, his is a government which came to power that very year on a promise of giving cotton farmers a price of Rs.2700 a quintal. At the time, they were getting a mere Rs.2200 a quintal. A sum the government conceded was quite uneconomical. Further, neither the State nor the Central government took any steps at all to counter the distortion of global cotton prices. Prices crashed as both the United States and the European Union piled on subsidies worth billions of dollars to boost their cotton sectors.

To top it all, the Deshmukh government withdrew the ‘advance bonus’ soon after coming to power. That brought the price down to just over Rs.1700 a quintal. And the Centre did not raise import duties on cotton despite desperate pleas for such an action. This allowed the large scale dumping of U.S. cotton on this country, further crushing the farmers here. No, Section 306 is not something Mr. Deshmukh’s government would want to look into too closely.

But to be fair to Mr. Deshmukh, he is neither unique nor alone in this mindset. There is something wrong with a society where suicide data are put together by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). The idea is in-built: suicide is a crime. From that flows Mr. Deshmukh’s simple notion of punishment. But he did not author the idea. He simply took it to unknown levels of insensitivity. With this statement, the Chief Minister outdid his previous effort when he made remarks about Vidharbha’s farmers that caused a furore. Remarks that suggested that they were both lazy and less than honest. Of course, he soon rallied to say he had been “quoted out of context.” (The Hindu, September 15, 2007). So maybe he will do so this time, too.

But he has certainly got the law out of context. What does Section 309 of the IPC really say? It states that “whoever attempts to commit suicide and does any act towards the commission of such an offence shall be punished with simple imprisonment for a term which may extend to one year or with a fine or with both.”

Fact: even the British Raj seems never to have used Section 309 against Mahatma Gandhi or other fasting leaders. And they had the excuse to do so when faced with, for instance, fasts unto death. This surely had less to do with humane behaviour than the hope that leaders like Gandhi would succeed in their fast unto death and rid the empire of a menace. Still the fact is: they did not resort to Section 309.

Mr. Deshmukh’s words suggest that he is holding himself back with much effort. If governments do start enforcing Section 309, the damage would be huge. For every farm suicide that occurs, there are a fairly large number of attempts that fail. Mostly, the police do not press the issue too hard. Even they see the ill logic of oppressing someone in misery who tries, but fails, to take his or her own life. (Such pressures have in a few cases, triggered a second — successful — attempt at suicide.) Following the ‘punishment’ logic would make life a living hell for those already in despair.

Decriminalising attempted suicide

For decades, social and legal workers and activists have struggled to decriminalise attempted suicide. One of them is Dr. Lakshmi Vijay Kumar, a consultant with the World Health Organisation on suicide research and prevention. As she puts it: “It’s a crazy law. One which only a handful of nations still retain. Most others have withdrawn it years ago. Apart from us, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Malaysia and Singapore seem to still have this kind of law. Sri Lanka too did but withdrew it in 1998. It’s a law that punishes those most in need of help. A move to repeal it went through the Rajya Sabha in 1974. The bill was also introduced in the Lok Sabha but that house was dissolved before it could see it through.” The Section was even struck down by a Supreme Court ruling in 1994. However, it was later reinstated by a full bench.

As we write, the Maharashtra Assembly is in session. In the tiny Assembly session ahead, the question of farm suicides is sure to crop up. Why is Maharashtra, with more dollar billionaires and millionaires than any other State in the country, home to the largest number of farmers’ suicides in India? Why is it that farm suicides in this State trebled between 1995 and 2005? Why did they go up so massively in a State where suicides amongst non-farmers fell marginally in the same period?

All the data on farm suicides carried in The Hindu (Nov.12-15) are from the National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. They are not the data of this newspaper. Nor of Professor K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS) who authored the study reported in the paper. They are government data. So if Mr. Deshmukh’s outfit has different numbers for the State Assembly, it could be in danger of committing contempt of the house.

Maybe someone in the house will raise other questions too. Queries that go, as they should, way beyond the suicides. The suicides are, after all, a tragic window to a much larger agrarian crisis. They are a symptom of massive rural distress, not the process. A consequence of misery, not its cause. How many more commissions will the government appoint to tell itself what it wants to hear? When will it address the problems of price, credit and input costs, for instance? When will it, if at all, reflect on the role of cash crops in the crisis? When will it push Delhi to set up a Centre-State price stabilisation fund? When will it dig its head out of the sand?

Friday, November 16, 2007

One farmer’s suicide every 30 minutes[15/11/07]

On average, one Indian farmer committed suicide every 32 minutes between 1997 and 2005. Since 2002, that has become one suicide every 30 minutes. However, the frequency at which farmers take their lives in any region smaller than the country — say a single State or group of States — has to be lower. Because the number of suicides in any such region would be less than the total for the country as a whole in any year. Yet, the frequency at which farmers are killing themselves in many regions is appalling.

On average, one farmer took his or her life every 53 minutes between 1997 and 2005 in just the States of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh). In Maharashtra alone, that was one suicide every three hours. It got even worse after 2001. It rose to one farm suicide every 48 minutes in these Big Four States, and one every two and a quarter hours in Maharashtra alone. The Big Four have together seen 89,362 farmers’ suicides between 1997 and 2005, or 44,102 between 2002 and 2005.

K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS), who has studied farmers’ suicides between 1997-2005 based on the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data, divides the States into four groups. The worst of these is Group II which includes, besides the Big Four, the State of Goa which shows a high farmers’ suicide rate (FSR) — that is, suicides per 1,00,000 farmers. However, Goa’s rate is based on tiny absolute numbers. All Group II States have high general suicide rates (GSR) — suicides per 1,00,000 population — and have seen large numbers of farm suicides.

Of these, Andhra Pradesh shows some decline in 2005. And the government claims the numbers have fallen further in 2006. But there is no NCRB data to support this as yet. In all, if the NCRB data are valid, then Andhra Pradesh saw 16,770 suicides between 1997 and 2005.Decline in Andhra Pradesh

Andhra Pradesh was the first State after the 2004 polls to appoint a commission to go into the agrarian crisis. Based on the commission’s advice, it also took some steps towards handling that crisis. It restored compensation for the suicides that had been stopped by the previous regime in 1998. It persuaded creditors to accept a one-time settlement of debt in several cases. This possibly helped see a decline after the terrible years of 2002-04. However, Andhra Pradesh has begun to mimic Maharashtra in one unhappy aspect. The number of “non-genuine” cases — those the government does not accept as distress-linked — keeps mounting each month while the “genuine” suicides decline.

There are other problems too. Several States, notably Maharashtra, have made identification of farmers’ suicides extremely difficult by using indicators that rule out vast numbers from being categorised as such. One problem with such corruption of data is that it will eventually reflect in and distort future NCRB reports as well.

Karnataka too records some decline in 2004 and 2005, after a disastrous five-year period. And the State’s 15 per cent increase in non-farmers committing suicide in the 1997-2005 period is five times higher than the rise in farmers’ suicides (3 per cent). But the damage of those earlier years was huge. Karnataka saw as many as 20,093 farm suicides in the period. Again, it is unclear whether the lower numbers for 2004-05 were largely due to policy measures or whether there have been new and creative accounting techniques.

“Madhya Pradesh appears to have long been a problem State for farmers, though this has not been so far acknowledged,” says Professor Nagaraj. “The increase in farm suicides over the nine-year period 1997-2005 is not so high, at 11 per cent, but the absolute numbers have been very high for a long period. Much higher than in many other States. However, here too, the rise in non-farmer suicides, at 48 per cent, is more than four times the increase in farmers’ suicides.” Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh) saw 23,588 farm suicides in the 1997-2005 period. However, Madhya Pradesh has mostly escaped the media radar as a farm crisis State. In Group II States, farm suicides as a percentage of total suicides reached 21.9 in 2005 against a national average of 15.5. In short, more than one of every five persons taking his or her life in these States that year was a farmer. Also, one in every four suicides in this group was committed using pesticide.

One State outside the Big Four that has seen high numbers of farmers’ suicides is Kerala. It saw a total of 11,516 in 1997-2005. Worse, many of these occurred in small districts such as Wayanad. Kerala shows a fluctuating but declining trend over the nine-year period. The years 1998 to 2003 were clearly its worst period. More than 70 per cent of its farm suicides occurred in those years. From 2004, the numbers begin to drop. So much so that unlike the Big Four, it shows no increases in farm suicides for the whole period. The post-2003 fall, in fact, makes its overall figure minus 7 per cent.

Kerala created a “Debt Relief Commission” soon after the change in government there in 2005. The Commission held a case by case scrutiny of the debt problem, while the government halted aggressive loan recovery measures by banks and money lenders. On the Commission’s advice, the government also decided to declare the entire Wayanad revenue district distress-affected.Kerala still vulnerable

The improvement is quite fragile and could easily see a downturn. Kerala’s farm suicide rate for the period is very high, and the State remains vulnerable to volatility in the prices of, for instance, coffee, pepper, cardamom or vanilla. A fragility enhanced by the fact that major relief on the debt front requires Central help. Besides, State bureaucracies are extremely hostile to debt relief for farmers. Also, India’s free trade agreements with nations and neighbours that produce the same cash crops as Kerala hurts badly. The State’s balance on the farm suicides front is very delicate. Complacence would be, literally, fatal.

Group I States are those which have very high general suicide rates. That includes Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, West Bengal, and Tripura. “However, Group I’s share of both total suicides and of farmers’ suicides declined between 1997 and 2005, even as that of Group II steadily rose,” points out Professor Nagaraj.

Group III States (Assam, Orissa, Gujarat, and Haryana) are those which have “moderate general and farm suicide rates,” while Group IV States (Bihar including Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh including Uttaranchal, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Punjab and Rajasthan) report “low general and farmers’ suicides rates.”

Generally speaking, the Gangetic plain region and eastern India have seen fewer farm suicides. States such as Uttar Pradesh (including Uttaranchal), Bihar (including Jharkhand) and Orissa report very few suicides of this kind. These States are in many respects the opposite of the Group II or ‘Suicide SEZ’ States. These are overwhelmingly food crop regions. They are not intensive input zones, and their costs of cultivation are much lower. Use of chemicals is not anywhere at the levels it is in the Group II States. Government support prices for food crop provide some minimal stability. And there is obviously a better water situation.

States such as Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan and Gujarat also report few farm suicides but their data have been challenged. Haryana, for instance, reports fewer suicides but its increase over the nine-year period was 211 per cent. This springs not from the recording of huge increases in recent years, but because the base year data appear highly flawed. For 1997, Haryana reports a spectacularly low 45 suicides. Which distorts the figure of increase in farm suicides across the period, pushing it upwards. “It could just have been that the counting operation was really shoddy or that it collapsed or was incomplete when data were sent in 1997,” says Professor Nagaraj. The numbers after the low 1997 figure remain roughly within a 170-210 range each year. Which again is strongly contested by farm unions and activists.

There are peculiar indications in Gujarat. Pesticide suicides — a common tool in farm suicides — are 84 per cent higher here than farm suicides. At the national level, they are just 28 per cent higher. Why is the gap three times bigger for Gujarat? Even for Group II States, pesticide suicides are only 21 per cent higher than farm suicides. Which raises the question whether several deaths in Gujarat ended up being recorded as just “pesticide suicides” without being acknowledged as suicides by farmers.

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

Maharashtra: ‘graveyard of farmers’ [14/11/2007]

30,000 farm suicides in a decade; Vidharbha worst place in nation to be a farmer.

Nearly 29,000 farmers committed suicide in Maharashtra between 1997 and 2005, official data show. No other State comes close to that total. This means that of the roughly 1.5 lakh farmers who killed themselves across the country in that period, almost every fifth one was from Maharashtra — which saw a 105 per cent increase in farm suicides in those nine years. More than 19,000 of those farmer suicides occurred from 2001 onwards.

These dismal findings emerge from a major study of official data on farm suicides by K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS). Professor Nagaraj has analysed data recorded by the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB), Ministry of Home Affairs, from 1997 to 2005 (see Table). The study begins with 1997 because that was the year when most States began reporting farm data regularly.

However, Maharashtra is a State that did report farm data in 1995 and 1996, too. If we include those two years, then the number of farm suicides in the 1995-2005 period was almost 32,000. An increase of over 260 per cent between those years. Maharashtra is one of the country’s richest States. Its capital, Mumbai, is home to 25,000 of India’s 100,000 dollar millionaires.

Professor Nagaraj’s study shows that of the almost 1.5 lakh farm suicides in India between 1997 and 2005, over 89,000 occurred in just four States: Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh). Importantly, Maharashtra accounts for a third of all farm suicides within these Big Four States. “This State,” says Professor Nagaraj, “could be called the graveyard of farmers.”

In terms of a percentage increase in farm suicides between 1997 and 2005, Andhra Pradesh’s figure is actually higher than that of Maharashtra. Andhra Pradesh saw a 127 per cent increase in farm suicides in the 1997-2005 period. Then what makes Maharashtra worst amongst the Big Four? In all the other three States, suicides by non-farmers also rose massively in this period. Non-farmer suicides shot up 48 per cent in Andhra Pradesh, 48 per cent in Madhya Pradesh, and 15 per cent in Karnataka. The crisis was more generalised across sections of society.

In Maharashtra, suicides by non-farmers actually saw a decline of 2 per cent in those years. That means the intensity of the crisis was borne almost entirely by the farming community. So farm suicides rose steeply, even as non-farm suicides fell marginally.

The percentage increase in farm suicides for Andhra Pradesh (127 per cent) was higher than in Maharashtra (105 per cent) if we take the 1997-2005 period. However, these are both States where the data go back to 1995. Taking that year as the base, the percentage increase of farm suicides in Maharashtra was 263 per cent over 1995-2005. For Andhra Pradesh, it was 108 per cent over the same period. This translates into a very high annual compound growth rate (ACGR) of 7.6 per cent in farmers’ suicides in Andhra Pradesh for the period 1995-2005. Which implies farm suicides there might double in 10 years if present trends hold. Maharashtra’s ACGR for the same period was 13.7. Which means farmers’ suicides here could double in six years, given the same trends.Door-to-door survey

Unlike for most States, some region-specific data on farm distress do exist in Maharashtra. Thanks to public action and activism, positive court intervention, and media pressure, the State Government was forced to keep some record, however flawed. Also, a paper by the then Divisional Commissioner, Amravati, S.K Goel, clearly recorded the situation in the Vidharbha region. Besides, the Maharashtra Government held the largest-ever door-to-door survey of its kind in the region in 2006. This study covered every farm household in Vidharbha’s six ‘crisis’ districts using 10,000 investigators. It captured a portrait of distress and crisis (The Hindu, Nov. 22, 2006).

It found that of the 17 lakh plus families covered, more than a fourth — that is, more than two million people — were “under maximum distress.” And more than three quarters of the rest were “under medium distress.” In short, almost seven million people were in distress. The major sources of such misery: debt and crop loss or crop failure (which often overlap). The pressure on farmers who cannot afford their daughters’ marriages. And rising health costs.

The paper by Dr. Goel, “Farmers’ Suicides in Maharashtra: An Overview,” placed some of this data on record. While his reading of some of the data does not hold up, his contribution to the study of the subject has been quite vital.

Among other things, the paper reveals that the total number of suicides in the six districts between 2001 and 2006 was extremely high at 15,980. Worse, the number went up from 2,425 in 2005 to 2,832 in 2006 — an increase of 407 in a single year. (And in 2006 both the Prime Minister’s and Chief Minister’s “relief packages” were at work.) The paper also confirms indebtedness as a factor in 93 per cent of farm suicides. The next highest factor being “economic downfall” — at 74 per cent.

However, only the state gets to decide which suicide is a “farmers’ suicide.” The Maharashtra Government’s efforts show much creative accounting. The Nagpur Bench of the Mumbai High Court compelled the government to maintain suicide statistics on its official website from mid-2006. But with a few exceptions, the media never really picked up the damaging data on the website. And the government was free to play with definitions of what was a “genuine” farm suicide.Jugglery

As a result, less than 20 per cent of the 15,980 suicides are by “farmers.” This, in overwhelmingly rural districts! (For instance, 80 per cent of Yavatmal’s population is rural.) And just a fraction of that — 1,290 cases — are accepted by the government as distress suicides worthy of compensation. This is achieved by inspired jugglery, as the accompanying table (I) shows.

The first columns give you total suicides each year. Take 2005 for instance, which saw 2,425 suicides in these districts. The next column is “Farmers’ Suicides.” Just 468 of them. Then an extraordinary column: “Family members’ suicides.” That figure is 559. That is, it holds that family members on the farm committing suicide are not farmers. This helps skim down the figure further. Next comes the total of these two followed by “Investigated cases.” The final column invents a new category unknown elsewhere: “Eligible suicides”. That is, suicides the government deems genuine and due for compensation. And so, for 2005, the suicides column that begins at 2,425 ends with 273. This amputated figure then, for propaganda purposes, becomes the number of “farmers’ suicides.” This way, a ‘decline’ in farm suicides is ‘established.’

The contortions are best seen in the category of “Eligible” suicides. Indeed, there is a whole separate table — not reproduced here — on “Percentage of eligible farmers suicides in six districts.” And of course, “Estimated eligible suicide cases” show a decline. So the number of suicides keeps mounting — but the number of farm suicides keeps falling! If accepted at face value, this jugglery would imply that only farmers are doing well.

Everybody else is sinking in Vidharbha. Read more seriously, the region specific data — viewed against the national and State figures — suggest that Vidharbha is today the worst place in the nation to be a farmer.

Farm suicides worse after 2001[13/11/07]

While the number of farm suicides kept increasing, the number of farmers has fallen since 2001, with countless thousands abandoning agriculture in distress.

Although National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data confirm an appalling 1.5 lakh farm suicides between 1997 and 2005, the figure is probably much higher. Worse, the farmers’ suicide rate (FSR) — number of suicides per 100,000 farmers — is also likely to be much higher than the disturbing 12.9 thrown up in the 2001 Census.

In the five years from 1997 to 2001, there were 78,737 farm suicides recorded in the country. On average, around 15,747 each year. But in just the next four years 2002-05, there were 70,507. Or a yearly average of 17,627 farm suicides. That is a rise of nearly 1,900 in the yearly averages of the two periods. Simply put, farm suicides have shot up after 2001 with the agrarian crisis biting deeper.

A comprehensive study of official data on farm suicides by K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS) pins down these and other figures. The data analysed by Professor Nagaraj are drawn from the various issues of Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India, a publication of the NCRB. But Professor Nagaraj also explains some of the reasons why the actual numbers and farmers’ suicide rate (FSR) could be far higher.

In 2001, when the farm suicides were not yet at their worst, the FSR at 12.9 was already higher than the General Suicide Rate (GSR) — suicides per 100,000 population — at 10.6. But even this higher suicide rate among farmers conceals a far worse reality. Firstly, the NCRB data seem to underestimate the number of farm suicides. This is because the criteria adopted for identifying a farm suicide at the State level are quite stringent. For instance, women and tenant farmers tend to get excluded from lists of farmers’ suicides. In those lists, only those with a title to land tend to be counted as farmers. On the other hand, the Census data are based on a very liberal definition of ‘cultivator.’Categories of cultivators

The 2001 Census gives data on two categories of cultivators: Cultivators among ‘main workers’ and those among ‘marginal workers.’ For the first group — cultivators among main workers — farming is the main activity. The second group includes those who practice cultivation only on a sporadic basis. However, both groups get counted as farmers. The net result of this is that while deriving the farm suicide rate from the NCRB and Census data, we are saddled with figures that undercount farm suicides but overcount the number of ‘farmers.’ Hence a value of 12.9 for the FSR is likely to be way below the mark. As Professor Nagaraj points out, “If we took only the cultivators among the main workers as farmers, the FSR increases dramatically to 15.8 which is nearly one and a half times the GSR of 10.6 in 2001.”

Secondly, the FSR is anchored in 2001 because that is the year of the Census. However, it was not one of the worst years in terms of farm suicides. Farm suicides in that year actually fell when compared to the previous year, 2000. But the very next year, in 2002, farmers’ suicides leapt by about 10 per cent. And the number of such deaths peaked in 2004. So while the number of farmers’ suicides shows a rising trend after 2001, the number of farmers may well have declined.

The trend of a decline in cultivators seems to have begun even earlier. The 1991 Census says there were 111 million cultivators among main workers. This fell to 103 million in the 2001 Census. This decline would surely have sharpened after 2001 as the farm crisis deepened. Certainly farming has no new takers.

As Professor Nagaraj’s study shows, the Annual Compound Growth rate (ACGR) for all suicides in India over the nine-year period 1997-2005 is 2.18 per cent. This is not very much higher than the population growth rate. For farm suicides, it is much higher, at nearly 3 (or 2.91) per cent. An ACGR of 3 per cent in farm suicides is more alarming as it applies to a smaller total of farmers each year. This means the farm suicide rate must have shot up after 2001.

Suicides by farmers went up 27 per cent during the 1997-2005 period. But non-farm suicides went up by 18 per cent. Indeed, the general suicide rate declined after 2001 — from 10.6 in 2001 to 10.3 in 2005. Which means the increase in general suicides has not kept pace with the increase in the general population. So by all accounts, while the number of farm suicides kept increasing, the number of farmers has fallen since 2001, with countless thousands abandoning agriculture in distress. Which would mean that farm suicides are mounting even as the farm population slowly declines.Huge differentials in numbers

Lastly, whether we take the farm suicide rate as 12.9 or 15.8, it is the figure for the country as a whole. That again hides huge differentials in the numbers and intensity of farm suicides across the country. There are States and regions in the country where the FSR is appallingly high. There are regions where it is mercifully still low.

Professor Nagaraj accordingly divided the States into four groups. Group I: States with very high general suicide rates. Group II: States with high general suicide rates and large numbers of farmers’ suicides. (This is the most important group.) Group 3: States with moderate general and farm suicide rates. And Group 4: States with low general and farm suicide rates (See Table).

What demarcates the Group II States — clearly the worst hit — is also the trend in suicides, which is most dismal there. This key group includes Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh) and Goa. (The last with tiny absolute numbers.) The ratio of farmers’ suicide rate to the general suicide rate was highest in this Group (see Table). The overall ratio of this group is 1.7. Which means the farm suicide rate in these States is 70 per cent higher than it is in their whole population.

Of the major States, Maharashtra has the worst figure with a ratio of farmers’ suicide rate to general suicide rate of 2.0. That is, one hundred per cent higher. This is followed by Karnataka with 1.6. Of the smaller States, Kerala (from Group I) has the awful figure of 4.7. But it also shows a decline from 2004. Puducherry shows up as the worst with 15.4. Of course, the last two have smaller absolute numbers.

The trend for Group II is most dismal. The AGCR for farm suicides in these States for the 1997-2005 period was 5.33. Or nearly double the national figure of 2.9. And if this trend holds, farm suicides in this group as a whole would double every 13 years. Among these States, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh would fare even worse.

Monday, November 12, 2007

Farm suicides rising, most intense in 4 States

In 2005, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh) accounted for 43.9 per cent of all suicides and 64 per cent of all farm suicides in the country.

Of the 1.5 lakh Indian farmers who took their own lives between 1997 and 2005, nearly two-thirds did so in just the States of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, and Madhya Pradesh (including Chhattisgarh). “What’s worse,” says K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS), “the trend for this group of States looks quite dismal. All four have, over the nine-year period, shown an ascending trend in farmers’ suicides.̶ 1; This emerges from the painstaking study on farmers’ suicides in India between 1997 and 2005 that Professor Nagaraj has just concluded. The study draws on data from the National Crime Records Bureau.

“They began keeping farm data only from 1995,” says Professor Nagaraj. “But significant States did not start reporting their data till about two years later. So the study begins with the year 1997. And 2005 is the last year for which such data were available nationally.” He has also drawn on the 2001 Census in order to calculate the suicide rate for farmers (FSR). That is, suicides per 100,000 farmers.Dramatic increase

The number of Indians committing suicide each year rose from around 96,000 in 1997 to roughly 1.14 lakh in 2005. In the same period, the number of farmers taking their own lives each year shot up dramatically. From under 14,000 in 1997 to over 17,000 in 2005. While the rise in farm suicides has been on for over a decade, there have been sharp spurts in some years. For instance, 2004 saw well over 18,200 farm suicides across India. Almost two-thirds of these were in the Big Four or ‘Suicide SEZ’ States.

The year 1998, too, saw a huge increase over the previous year. Farm suicides crossed the 16,000 mark, beating the preceding year by nearly 2,400 such deaths. Farm suicides as a proportion of total suicides rose from 14.2 in 1997 to 15.0 in 2005.

Professor Nagaraj also points to the Annual Compound Growth Rate (ACGR) “for suicides nationally, for suicides amongst farmers, and those committed using pesticides.”

The ACGR for all suicides in India over a nine-year period is 2.18 per cent. This is not very much higher than the population growth rate. But for farm suicides it is much higher, at nearly 3 (or 2.91) per cent. Powerfully, the ACGR for suicides committed by consuming pesticide was 2.5 per cent. Close to the figure for farmers.

Such suicides are often linked to the farm crisis, with pesticide being the handiest tool available to the farmer. “There are clear, disturbing patterns and trends in both farmers’ suicides and pesticide suicides,” says Professor Nagaraj.Not the full picture

Alarming though that is, it still does not capture the full picture. The data on suicides are complex, and sometimes misleading. And not just because of the flawed manner in which they are put together, or because of who puts them together. There are other problems, too. Farmers’ suicides as a percentage of total farmers is hard to calculate on a yearly basis. A clear national ‘farm suicide rate’ can be derived only for 2001. That is because we have the Census to tell us how many farmers there were in the country that year. For other years, that figure would be a conjecture, however plausible.

But even in 2001, when the farm suicides were not yet at their worst, the farm suicide rate (FSR) at 12.9 was much higher than the general suicide rate (GSR) at 10.6 for that year. But the GSR slowed down after that to 10.3 by 2005 even as the total number of suicides went up. It means that the increase in the number of general suicides did not keep pace with the growth in general population. But the FSR seems to have risen more steeply after 2001. By all accounts, while the number of farm suicides kept increasing, the number of farmers has fallen since 2001, with countless thousands abandoning agriculture.

In 2005, the Big Four or ‘Suicide SEZ’ States accounted for 43.9 per cent of all suicides and 64.0 per cent of all farm suicides in the country. By contrast, a group of States with the highest general suicide rates — including Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal, Tripura, and Puducherry — accounted for 20.5 per cent of farm suicides in India. “Their share of both total suicides and of farmers’ suicides declined between 1997 and 2005 even as that of the Big Four steadily rose,” points out Professor Nagaraj.

To the extent the media have covered the farm crisis, their focus has been on farm suicides in four States — Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Kerala. Very broadly speaking, that appears to have been right. All have very high rates of farmers’ suicides. Madhya Pradesh though, is a major State showing such trends which has received scant attention. (Among smaller regions and States, Goa, and Puducherry show extremely high farm suicide rates but on tiny absolute numbers.)

It is important that the figure of 1.5 lakh farm suicides is a bottom line estimate. It is by no means accurate or exhaustive. There are inherent and serious inaccuracies in the NCRB data as they are based on ground data that exclude large groups of people. As Professor Nagaraj puts it: “There is likely to be a serious underestimation of suicides, particularly of farmers’ suicides, in these reports. The most important problem is the way a farmer is defined at the ground level: as someone who has a title to land. This is likely, for instance, to leave out tenant farmers and, particularly, women farmers.”

The quality of reporting also varies from State to State. For instance, Haryana shows a very low ratio of farm suicides to general suicides. This conflicts with other assessments of the problem in that State. Data from Punjab have also been highly contested by groups monitoring the farm crisis there.

However, even in this flawed data, the trends are clear and alarming. But what has driven the huge increase in farm suicides, particularly in the Big Four or ‘Suicide SEZ’ States? “Overall,” says Professor Nagaraj, “there exists since the mid-90s, an acute agrarian crisis. That’s across the country. In the Big Four and some other States, specific factors compound the problem. These are zones of highly diversified, commercialised agriculture. Cash crops dominate. (And to a lesser extent, coarse cereals.) Water stress has been a common feature — and problems with land and water have worsened as state investment in agriculture disappears. Cultivation costs have shot up in these high input zones, with some inputs seeing cost hikes of several hundred per cent. The lack of regulation of these and other aspects of agriculture have sharpened those problems. Meanwhile, prices have crashed, as in the case of cotton, due to massive U.S.-EU subsidies to their growers. Or due to price rigging with the tightening grip of large corporations over the trade in agricultural commodities.”Debt trap

“From the mid-‘90s onwards,” points out Professor Nagaraj, “prices and farm incomes crashed. As costs rose — even as bank credit dried up — so did indebtedness. Even as subsidies for corporate farmers in the West rose, we cut our few, very minimal life supports and subsidies to our own farmers. The collapse of investment in agriculture also meant it was and is most difficult to get out of this trap.”

Nearly 1.5 lakh farm suicides from 1997 to 2005[front page-hindu-12/11/2007]

P. Sainath

Nearly 1,50,000 Indian farmers committed suicide in nine years from 1997 to 2005, official data show. While the suicides occurred in many States, nearly two-thirds of such deaths were concentrated in five States where just a third of the country’s population lives. This means that farm suicides occurred in these (mainly cash crop) regions with appalling intensity.

The five States are Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh (including Chattisgarh) and Kerala. Of these, only Kerala showed no sustained increase in the number of yearly farm suicides over this period. That was mainly because of a decline after 2003, which was that State’s worst year. Maharashtra, for which data exists from 1995, is by far the worst-hit. Farm suicides there more than trebled from 1083 in 1995 to 3926 in 2005.

Suicides as a whole rose nationally in the 1997-2005 period. But the rate of increase in farm suicides was far higher than the rate of increase in suicides by non-farmers. In Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Madhya Pradesh, the percentage increase in farm suicides were more than double the increase in non-farm suicides in this period.

While suicides by non-farmers went up by 23 per cent in the Big Four States, farm suicides went up by 52 per cent. Indeed, these States might be termed the “Suicide SEZ” or “Special Elimination Zone” for farmers this past decade. In 1997, these States accounted for 53 per cent, or just over half of all farm suicides in the country. By 2005, it was 64 per cent.

That is, in less than a decade, their share of farm suicides, already disproportionately high, leapt to nearly two-thirds.

These and other grim findings emerge from a comprehensive study of official data on farm suicides by Professor K. Nagaraj of the Madras Institute of Development Studies (MIDS).

The data analysed by him were drawn from various issues of Accidental Deaths and Suicides in India.

This is a publication of the National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. The period covered by the study is from 1997-2005.

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Indexing inhumanity, Indian style

It took minutes for the top guns to swing into action when the Sensex fell by several hundred points. But no Minister came forward to calm the nation when

It all happened around the same time. The day the Sensex crossed 19,000,

Next came the fall of several hundred points in the Sensex. That is, barely a couple of days later. It took minutes for the top guns to swing into action. Fingers were in every dyke. Finance Minister P. Chidambaram lost no time in reassuring worried investors via the media. Other top officials were all over television, doing the same. “FM soothes the Market’s nerves” ran the ticker. The barrage — both media and official — kept up through the day. The panels of experts convened to celebrate the 19K summit were reconvened to explain why they’d tripped off the cliff. They then droned on about the merits of P-Notes, regulation and the future. What stood out, of course, was the swiftness of both government and media response to each twitch in the index.

No Minister came forward to calm the nation when

You’d think it was an issue worth some attention. But it was hard to find panels debating this on television. Or any editorials in the newspapers doing the same. No Ministers or top babus soothing the nerves of the hungry. No experts with furrowed brows warning that the trends could continue, even worsen.

The GHI is by no means the only measure of what’s happening. The United Nations’ Food & Agriculture Organisation put it simply in 2006. Its State of

There was also another link begging to be made. Not just between the Sensex and hunger stories. Let’s revert to the latest maternal mortality figures released by the WHO and others. Some 536,000 women died in childbirth in 2005. Of these, every fifth one of them, at least, was an Indian. That is, 117,000 of them. A total that could only be matched by

If we were to look at specific groups or communities, this would be even clearer. Let alone on the hunger index,

That’s quite easy to believe.

And so it is in

The furore now on the import of wheat is welcome. At least the media have begun to look at the issue. But surely, it is also worth discussing how we came to import wheat in the first place. And how a nation with so many in hunger ended up exporting millions of tonnes of grain this decade. That too, at prices lower than those we offer to millions of poor people in this country.

New heights of misery

And no matter how the Sensex is doing, the misery index for the poor scales new heights in one sector after another. Health costs still mount. They push people into debt even faster than before. A study done for the WHO in six Indian States found that 16 per cent of households it looked at were pushed below the poverty line by heavy medical costs. Nearly 10,000 families from lower income groups were covered by the survey for the years 2002-05. Some 12 per cent had to sell their assets to meet health expenses. Over 43 per cent had to resort to loans for the same reasons.

Our answer to this has been: more of the same. More privatisation. Less and less of a public health system. In Mumbai, extortion by hospitals has become so frequent as to actually find mention in the media. But journalists do not get to make the link between the gutting of public services and the public’s misery. Much less can they track this in terms of private profiteering. That would go against the publication or channel’s stand of privatisation as a cure for all ills.

More than once this year, the Bombay High Court has warned hospitals against the cruel practice of holding back the body of a patient — demanding lakhs of rupees from the family before returning it. It still happens, though. Now even at government hospitals leased out to private managements. So a low income family is suddenly told it owes the hospital a huge sum of money. And that the body of its five-year-old girl will be released only when that sum is paid. A fine example of public-private partnership as it works today.

‘Incredible India’ right here at home

| The week-long ‘Incredible |

Those focussed on the $10 million event in

The rice at Rs.2 a kilo annoyed the opposition Telugu Desam Party (TDP). After all, its founder, N.T. Rama Rao (NTR), was the true author of the scheme. But the TDP leaders had to be cautious about describing this as ‘stealing our clothes.’ For, their own government had shed those clothes with alacrity in the post-NTR era. So, instead, they announced ‘nine hours of free power daily for farmers’ — the very first policy the Congress signed into effect on taking power in 2004.

The TDP also promised farmers loans at four per cent interest. Not to be left out, the “Loksatta,” a movement that decries the populist stunts of other parties and which sees itself as cleaning up politics, showed itself as a force with a difference. A one-hour difference. It offered eight hours of free power as against the more lavish nine hours of the TDP. And, of course, rice at Rs.2 a kilo. The Telangana Rashtriya Samiti closed the bidding at 12 hours of free power for farmers. The TDP topped it off with the promise of three cents of land for poor urban families to build homes.

To gain a sense of just how incredible

Suddenly, it is to cover all districts of the country. The media say this happened because the request came from Rahul Gandhi. Well, good for him. Maybe, he can even get the government to fund it better. And extend it to all seeking work, while raising the number of work days. What’s incredible, though, is the instant conversion of the Prime Minister and his Finance Minister to avid fans of a programme they cared little for and adopted under duress from their allies.

No less impressive is the sudden hike in the minimum support price for wheat, rice and other crops. Till this moment, the government was happy to import wheat from

In

Only weeks earlier, the Chief Minister was in danger of losing his job for all the opposite reasons. He had scoffed at the farmers of Vidharbha — standing right in the zone of their suffering — and mocked their “innovative” ways of cheating. The uproar over those remarks drew the usual “quoted out of context” defence.

But all that is past now. No context is greater than the poll context. And if you are Chief Minister of one of the country’s richest States, it’s not a context you want to be thrown out of.

Meanwhile, the TDP in Andhra Pradesh finds that the Congress selling rice at Rs.2 a kilo is “panic reaction.” The idea had always been a TDP original. In truth, the TDP, while in office, had done away with the move after NTR’s time. It had forced a number of other costs on its people. Utility rates were hiked massively, sparking major State-wide protests. User charges were imposed on poor patients at government hospitals. The hospitals themselves were being set up for a transfer to private control. But now the party wishes to provide “quality power supply to the farm sector.” And pledges “to halt the auction of Government land” and check the growth of “shops selling liquor.”

The crisis in Karnataka also has firm roots in Incredible (or Electoral)

On the Ramar Sethu issue, alas, Incredible India has lost its way. When mythology takes over, it’s hard to discuss more vital problems of unique marine parks or the fate of local fishermen. If countless millennia of deposits and sediment formed such a bridge, it stands to reason that process will continue. So it’s worth pondering the fortune you will spend each year on cleaning up your planned route. Instead, we’re stuck with the mythology. But for the BJP, that’s Incredible India.

Impact on media

Incredible

The politicians are in fact way ahead of the media. At least in sensing public concerns and moods. They do not rely on SMS polls with a sample size of zilch, which declare with certainty that 97 per cent of Indians think that Thursday is better than Wednesday. Media antennae are far more crippled than those of the politicians they despise. Remember those magisterial pronouncements of the mega-pundits on the eve of the 2004 polls? All those they hope no one will recall the next time around? The most famous one was this — and it came from a highly visible media personality less than a hundred hours before the results were out:

“The era of the massive election rally has long been over. People now have work to do. This election was fought more in the media than in the streets. Television is now the new electoral battleground and, as with more developed democracies, will increasingly replace public meetings and door-to-door campaigns as the mode of campaigning. A recent … opinion poll has clearly shown that a large majority of voters now make up their minds on the basis of what they learn from the media.”

The decade of our discontent

| Sixty years on, rural |

Rural

The first lead story on the front page of a major English daily four weeks ago was striking. A young man from

It surely reflects something. A class exists to whom it is perfectly natural for a leading Indian magazine to act as luxury scout. Its publisher’s letter tells them that “for $115,000 a box, 500 limited edition Dragon Gurkha cigars are now available. In 80 year old camelbone boxes that once belonged to a Rajasthani ruler.”

The average monthly per capita expenditure (MPCE) of the Indian farm household is a long way from Rs.15 lakh. And further from $115,000. It is, in fact, Rs.503. Not far above the rural poverty line. And that’s a national average, mixing both giant landlords and tiny landholders. It also includes States like Kerala where the average is nearly twice the national one. Remove Kerala and

About 60 per cent of that Rs.503 is spent on food. Another 18 per cent on fuel, clothing, and footwear. Of the pathetic sum left over, the household spends on health twice what it does on education. That is Rs.34 and Rs.17. It seems unlikely that buying unique cellphone numbers is set to emerge a major hobby amongst rural Indians. There are countless households for whom that figure is not Rs.503, but Rs.225. There are whole States whose average falls below the poverty line. As for the landless, their hardships are appalling.

It is not that inequality is new or unknown to us. What makes the last 15 years different is the ruthlessness with which it has been engineered. The cynicism with which it has been constructed. And the scale on which it now exists. And that’s at all levels, even at the top. As Abhijit Banerjee and Thomas Piketty put it in a paper on “Top Indian Incomes 1956-2000,” “The rich (the top 1 per cent) substantially increased their share of total income [in the reform years]. However, while in the 1980s the gains were shared by everyone in the top percentile, in the 1990s it was only those in the top 0.1 per cent who made big gains.”

“The average top 0.01 per cent income was about 150-200 times larger than the average income of the entire population during the 1950s. This went down to less than 50 times as large by the early 1980s. But went back to being 150-200 times larger during the late 1990s.” All the evidence suggests it has gotten worse since then.

Industry’s hostile response to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh’s meek comments on CEO salaries is just a sign of how entrenched such privilege now is. The editorials of most newspapers blew Dr. Singh out of the water. So it is odd and worth noting, that one of the very best pieces on concentration of wealth in recent times comes from the Executive Director of Morgan Stanley. (The Economic Times, July 9, 2007). “We believe,” writes Chetan Ahya, “that the social pressure arising from widening inequality has increased in the past few years, driven by globalisation and the rise of capitalism.” He finds the “rising social challenge on account of the rise in inequality” a worrying trend. He also finds that “the inequality gap in wealth is even starker … Our analysis indicate an increase in wealth of over $1 trillion (over 100 per cent of GDP) in the past four years — and that the bulk of this gain has been concentrated within a very small segment of the population.” Mr. Ahya rightly sees “social and political upheaval,” as the outcome of some directions we are taking. As in the case of farmers and SEZs.

Structural inequalities

All this comes atop existing structural inequalities in rural

Even at the start of the reforms period, the bottom half of rural households accounted for less than 3.5 per cent of total land ownership. The top ten per cent of households owned well over 50 per cent. That’s for all lands as a whole. If we took into account only irrigated land, the picture is more frightening. Add productive assets, and it gets still worse. In one estimate, over 85 per cent of rural households are either landless, sub-marginal, marginal or small farmers. Nothing has happened in 15 years that has changed that situation for the better. Much has happened to make it a lot worse.

The direction of policy on farming — central to rural

The early decades were at least decades of hope. There were improvements, significant if not impressive. In literacy, life expectancy, and other human development indicators. There was a sense that “

Sixty years on, rural

A credit squeeze has pushed lakhs of farmers into bankruptcy. This after encouraging, even pushing them towards high-cost cash crop cultivation with its attendant risks. In Kerala of 2003-04, raising an acre of vanilla cost 15 to 20 times what it took to raise an acre of paddy. But farmers were asked to rush in regardless. The price of vanilla has sunk and the credit flow has stopped. And several such growers have taken their own lives.

We fail to invoke even those measures the blatantly unfair WTO allows us; this means the prices our own farmers get for products like cotton collapses by the season. The huge subsidies attached to

The government tells us over 112,000 farmers have committed suicide since 1993. A gross underestimate but the figure is bad enough. These are suicides driven by debt. And the indebtedness of the peasantry, so the National Sample Survey tells us, has almost doubled in the past decade.

It is not as if there is no resistance, no voices raised. The people have spoken to their governments and all of us in election after election. In protest after protest. And good things, too, have happened. Like the NREGA. But the larger direction is overwhelming. And it is one that races towards catastrophe, disaster having already been achieved. We, however, are more interested in the cellphone number worth Rs.15 lakh. And maybe there’s a point in that. The ‘fancy’ number was purchased on borrowed money. Our orgy in inequality plays out on borrowed time.

Nine decades of non-violence

Countless rural Indians sacrificed much for

We were sitting in the tent, they tore it down. We kept sitting," the old freedom fighter told us. "They threw water on the ground and at us. They tried making the ground wet and difficult to sit on. We remained seated. Then when I went to drink some water and bent down near the tap, they smashed me on the head, fracturing my skull. I had to be rushed to hospital."

Baji Mohammed is one of

No hatred in his heart

There is not an iota of anger as he describes the event. No hatred towards the RSS or Bajrang Dal that led the attack. Just a gentle old man with a charming smile. And a firm Gandhi bakht. He's a Muslim who heads the anti-cow slaughter league of Nabrangpur. "After the attack, Biju Patnaik came to my home and scolded me. He was worried about my being active even in peaceful protest at my age. Earlier, too, when I did not accept this freedom fighter's pension for twelve years, he chided me."

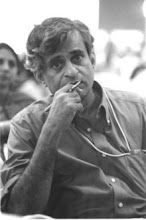

![]() Baji Mohammad at home in Nabrangpur, Orissa with his most precious possession: a photo showing him in one of Mahatma Gandhi's protest marches.

Baji Mohammad at home in Nabrangpur, Orissa with his most precious possession: a photo showing him in one of Mahatma Gandhi's protest marches.

Picture: P Sainath.

Baji Mohammed is a colourful remnant of a dying tribe. Countless rural Indians sacrificed much for

"I was studying in the 1930s, but did not make it past matric. My guru was Sadashiv Tripathi who later became Orissa Chief Minister. I joined the Congress Party and became president of its Nabrangpur unit [then still a part of Koraput district]. I made 20,000 members for the Congress. This was a region of great ferment. And it came fully alive with satyagraha."

However, while hundreds marched towards Koraput, Baji Mohammed headed elsewhere. "I went to Gandhiji. I had to see him." And so he "took a cycle, my friend Lakshman Sahu, no money, and went from here to

"Desai told us to talk to him during his 5 p.m. evening walk. That's nice, I thought. A leisurely meeting. But the man walked so fast! My run was his walk. Finally, I could no longer keep up and appealed to him: Please stop: I have come all the way from Orissa just to see you."

"He said testily: "what will you see? I too, am a human being, two hands, two legs, a pair of eyes. Are you a satyagrahi back in Orissa?' I replied that I had pledged to be one."

"Go,' said Gandhi. "Jao, lathi khao. (Go and taste the British lathis.) Sacrifice for the nation.' Seven days later, we returned here to do exactly as he ordered us." Baji Mohammed offered satyagraha in an anti-war protest outside the Nabrangpur Masjid. It led to "six months in jail and a Rs. 50 fine. Not a small amount those days."

More episodes followed. "On one occasion, at the jail, people gathered to attack the police. I stepped in and stopped it. "Marenge lekin maarenge nahin,' I said. (We shall die, but we shall not attack.)"

"Coming out of jail, I wrote to Gandhi: what now? And his reply came. "Go to jail again.' So I did. This time for four months. But the third time, they did not arrest us. So I asked Gandhi yet again: now what? And he said: "take the same slogans and move amongst the people.' So we went 60 km on foot each time with 20-30 people to clusters of villages. Then came the Quit India movement, and things changed."

"On August 25, 1942, we were all arrested and held. Nineteen people died on the spot in police firing at Paparandi in Nabrangpur. Many died thereafter from their wounds. Over 300 were injured. More than a thousand were jailed in Koraput district. Several were shot or executed. There were over a hundred shaheed (martyrs) in Koraput. Veer Lakhan Nayak [legendary tribal leader who defied the British] was hanged."

Baji's shoulder was shattered in the violence unleashed against the protesters. "I then spent five years in Koraput jail. There I saw Lakhan Nayak before he was shifted to Berhampore jail. He was in the cell in front of me and I was with him when the hanging order came. What should I tell your family, I asked him. "Tell them I am not worried,' he replied. 'Only sad that I will not live to see the swaraj we fought for.'" Baji himself did. He was released just before Independence Day - "to walk into a newly free nation." Many of his colleagues, amongst them future Chief Minister Sadashiv Tripathi, "all became MLAs in the 1952 elections, the first in free

"I did not seek power or position," he explains. "I knew I could serve in other ways. The way Gandhi wanted us to." He was a staunch Congressman for decades. "But now I belong to no party," he says. "I am non-party." It did not stop him from being active in every cause which he thought mattered to the masses. Right from the time "I took part in the bhoodan movement of Vinoba Bhave in 1956." He was also supportive of some of Jayaprakash Narayan's campaigns. "He stayed here twice in the 1950s." The Congress asked him to contest elections more than once. "But me, I was more sewa dal than satta dal. (More service oriented than power seeking.)"

Greatest moment

For freedom fighter Baji Mohammed, meeting Gandhi was "the greatest reward of my struggle. What more could one ask for?" His eyes mist over as he shows us pictures of himself in one of the Mahatma's famous protest marches. These are his treasures, having gifted away his 14 acres of land during the bhoodan movement. His favourite moments during the freedom struggle? "Every one of them. But of course, meeting the Mahatma, hearing his voice. That was the greatest moment of my life. The only regret is that his vision of what we should be as a nation, that is still not realised."

AGRO CRISIS

Several women in Karnataka's Mandya district like Jayalakshmamma, whose husband committed suicide four years ago, still stand up to the unending pressure with incredible resilience, writes P Sainath.

When Jayalakshmamma finishes her 12 hours of labour - on those days she can find work - she's entitled to less than a fourth of the rice given to a convict in prison. In fact, the rice she gets on average for a whole day is far less than what the incarcerated offender gets in a single meal.

Jayalakshmamma is not a convict in prison. She's a marginal farmer whose husband H.M. Krishna, 45, killed himself in Huluganahalli

"Four kilograms a month means about 135 grams a day," says T. Yashavantha, who is from a farming family of the same district. He is also State vice-president of the Students Federation of India. "Even an undertrial or convict gets more." What's more, they get cooked rice. She gets four kg of grain. Jail diets in the State vary according to whether the prisoner is on a "rice diet," a "ragi diet" or a "chapati diet." Jail officials in

The convict doing rigorous imprisonment does eight hours of labour. Jayalakshmamma does 12 or more. "But her entitlement is 45 grams per meal if she has three a day," points out Mr. Yashavantha. She doesn't have the time, though, to make comparisons. Her daughter now works at breadline wages in a

They own around 0.4 acres and had leased two acres before

"I wanted Nandipa to study. But he was in despair. Three years ago, then aged 12, he ran off to

"All widows have problems. But those bereaved by the farm crisis suffer worse," says Sunanda Jayaram, president of the women's wing of the Karnataka Rajya Ryuthu Sangha (Puttanaiah group) "Even after losing her husband she has to maintain his father and mother, her own children and the farm - with no economic security for herself. And she is saddled with his debts. Her husband took his own life. She will pay the price all her life."

In Bidarahosahalli village, Chikktayamma's state exemplifies this. Her husband, Hanumegowda, 38, killed himself in 2003. "The debts are all we're left with," she says, without self-pity. "What we earn won't pay off even the interest on loans to the money lenders." She's struggled to educate her three children - who might be forced to drop out though all want to study further. "The girls should study, too. But later, we'll have to raise lots of money for their marriages as well."

One girl, Sruthi, has done her SSLC exams and another, Bharathi, is in the second year of her pre-university course. Her son Hanumesh is in the 8th standard. Her husband's mother and a couple of other relatives also live in this house. Chikktayamma is the sole breadwinner for at least five people. "We have only 1.5 acres [on part of which she grows mangoes]. So I also work as a labourer when I can for Rs. 30 a day. I had a BPL card but they [the authorities] took it from me saying `we'll give you a new card.'" It never came back, says Mr. Yashavantha. "Instead, they gave her an APL [above the poverty line] one."

Huge debt

In Huligerepura, Chenamma and her family grapple with a debt of over Rs.2 lakh left by her husband Kadegowda, 60, who took his life four years ago. "Sugarcane just sank and it crushed him," says his son Sidhiraj. "We have only three acres," says Chenamma. "It's hard to generate a living from that now." But she and her sons still try. And the family plans to shift to paddy this year.

In Thoreshettahalli, Mr. Yashavantha's father, Thammanna, a farmer for decades, says the farm crisis is biting deep. "Most cane growers are not recovering the cost of production. Input costs go upwards, incomes downwards. Also, some 40 borewells were drilled in this village last month but only one succeeded. People are giving up. You will find farmland lying unused even during season."

What about self-help groups? Jayalakshmamma has paid an initial amount "but the group has not yet launched. And I cannot afford the Rs.25 a week. Nor the 24 per cent interest each year." Chikktayamma cannot think of making such payments regularly. "The SHG concept is a good one," says KRRS leader K.S. Puttannaiah. "But in some cases, they've also become moneylenders. Meanwhile, after the initial compensations, the State has no plan for widows and orphans of farm suicides. When have they even thought about it?"